Fils cadet d’un marchand de Aichi adopté par une autre famille marchande, Iwai Eiichi part étudier en 1918 à Shanghai au Tōa dōbun shoin 東亜同文書院 (Institut de la culture commune est-asiatique), école fondée en 1900 pour former des spécialistes japonais de la Chine. Sorti diplômé en 1921 de la filière commerce (shōmuka 商務課) de l’établissement shanghaïen, il intègre la même année le ministère des Affaires étrangères (gaimushō 外務省) comme simple interprète. Iwai entame alors une carrière au cours de laquelle il séjourne en tout dix-neuf années en Chine, contre cinq années au Japon. D’abord posté à Chongqing avant d’être muté à Shantou 汕頭 (Guangdong) en 1922, Iwai rentre en 1924 dans l’archipel, où il se marrie et travaille pour la 1ère section du Bureau de l’information (jōhōbu dai ichi ka 情報部第一課) de son ministère. En 1926, il est envoyé au consulat de Changsha (Hunan) comme chancelier (shokisei 書記生) ; poste subalterne réservé au personnel consulaire, distinct du prestigieux corps diplomatique, dont la plupart des titulaires en Chine étaient, comme Iwai, issus du Tōa dōbun sho-in. Alors que l’Expédition du Nord s’accompagne d’une montée du patriotisme chinois, les résidents japonais sont pris à partie par la population locale, notamment à Wuhan où éclate, le 3 avril 1927, l’Incident de Hankou (Hankō jiken 漢口事件), mais aussi à Changsha. Entre avril et août, Iwai et sa famille se réfugient dans la concession japonaise de Hankou.

Iwai se fait remarquer à cette époque en publiant deux essais dans la revue Shina 支那 (Chine) éditée par l’Association pour la culture commune est-asiatique (Tōa dōbun-kai 東亜同文会), maison mère du Tōa dōbun shoin. Le premier, “Shina kokusai hogoron 支那国際共同保護論” (La protection commune internationale de la Chine), paru en juin 1928, propose de retourner le projet impérialiste de “gestion internationale de la Chine”, au profit d’une approche “amicale”. Selon Iwai, il en va de la responsabilité du Japon et des autres puissances de venir en aide à la population chinoise en organisant un sommet mondial guidé par des valeurs “humanistes” qui enverrait en Chine un contingent international chargé de rétablir l’ordre. Le second article, “Manshū mondai kaiketsu no kyakkan teki kōsatsu 満洲問題解決の客観的考察” (Réflexions objectives sur la résolution du problème mandchou), paraît en octobre 1929, à la veille du 3e sommet de l’Institute of Pacific Relations (Taiheiyō mondai chōsa-kai 太平洋問題調査会) organisé à Kyoto, qui voit la question de la Mandchourie être âprement débattue entre Matsuoka Yōsuke 松岡洋右 (1880-1946) et le chef de la délégation chinoise Xu Shuxi 徐淑希 (1892-1982). Iwai y défend une solution “diplomatique” censée éviter la montée des tensions provoquées par la politique de centralisation du Gouvernement national à la suite de l’assassinat de Zhang Zuolin, d’une part, et l’expansionnisme de l’Armée du Guandong stationnée en Mandchourie, d’autre part. Comme d’autres dirigeants japonais à l’époque, il propose que son pays acquière la Mandchourie, dont il considère qu’elle revient de droit au Japon qui a consenti un grand sacrifice pour l’emporter contre la Russie en 1905. Revenant sur cette position dans ses mémoires publiés en 1983, Iwai affirme même que, sans ce sacrifice, les province du Nord-Est n’auraient jamais fait partie du territoire national chinois tel qu’il est délimité en 1945. Cette voie diplomatique défendue en 1929 est balayée par l'”Incident de Mukden“, le 18 septembre 1931.

Après deux ans passés à Tokyo à la Section des télécommunications (denshin-ka 電信課) – période durant laquelle il prend la tête de la grève contre la baisse des salaires du Gaimushō, Iwai repart dans une Chine en plein tumulte. Il arrive à Shanghai en février 1932, quelques jours après le déclenchement des combats qui voient les troupes chinoises opposer une résistance farouche au coup de force nippon. Isolée sur la scène internationale et chinoise, la diplomatie japonaise ne dispose pas de moyens suffisants pour collecter des renseignements sur les pays ennemis. Avec le soutien de l’ambassadeur Shigemitsu Mamoru, Iwai soumet alors à la direction du ministère un plan visant à doter la légation de Shanghai d’un Bureau de l’information (jōhōbu 情報部). Sous la houlette de son chef, Suma Yakichirō 須磨弥吉郎 (1892-1970), Iwai obtient des renseignements révélant l’existence d’une organisation secrète formée en soutien à Jiang Jieshi par des officiers issus de l’Académie militaire de Huangpu, plus tard connue sous le nom de “Chemises bleues” (lanyishe 藍衣社). Il publiera en avril 1942 une traduction chinoise de ce rapport – Lanyishe neimu 藍衣社內幕 (Les coulisses de la Société des chemises bleues), qui rencontrera un grand succès en zone occupée. Autre fait d’arme : lors de l’incident diplomatique provoqué par la publication, le 4 mai 1935, d’un article tournant en dérision l’empereur Shōwa dans la revue shanghaienne Xinsheng 新生 (Vie nouvelle), Iwai est en mesure de prouver que l’article en question a été autorisé par le Comité de censure du Bureau central du GMD et décide de communiquer cette information à l’attaché militaire adjoint de la légation japonaise, Kagesa Sadaaki. Les deux hommes ont fait connaissance en août 1934 à l’instigation de Kawai Tatsuo 河相達夫 (1889-1965), qui remplace Suga en novembre 1933 à la tête du Bureau de l’Information. Convaincu qu’il tient là une occasion en or d’obliger le GMD à cesser sa propagande anti-japonaise, Iwai cherche à contourner ses propres supérieurs qui s’inquiètent que cet incident ne menace la détente sino-japonaise. Par l’intermédiaire de Kagesa, il obtient que l’armée fasse pression sur le régime nationaliste, conduisant le secrétaire général du Bureau central du GMD Ye Chucang 葉楚傖 à présenter des excuses écrites.

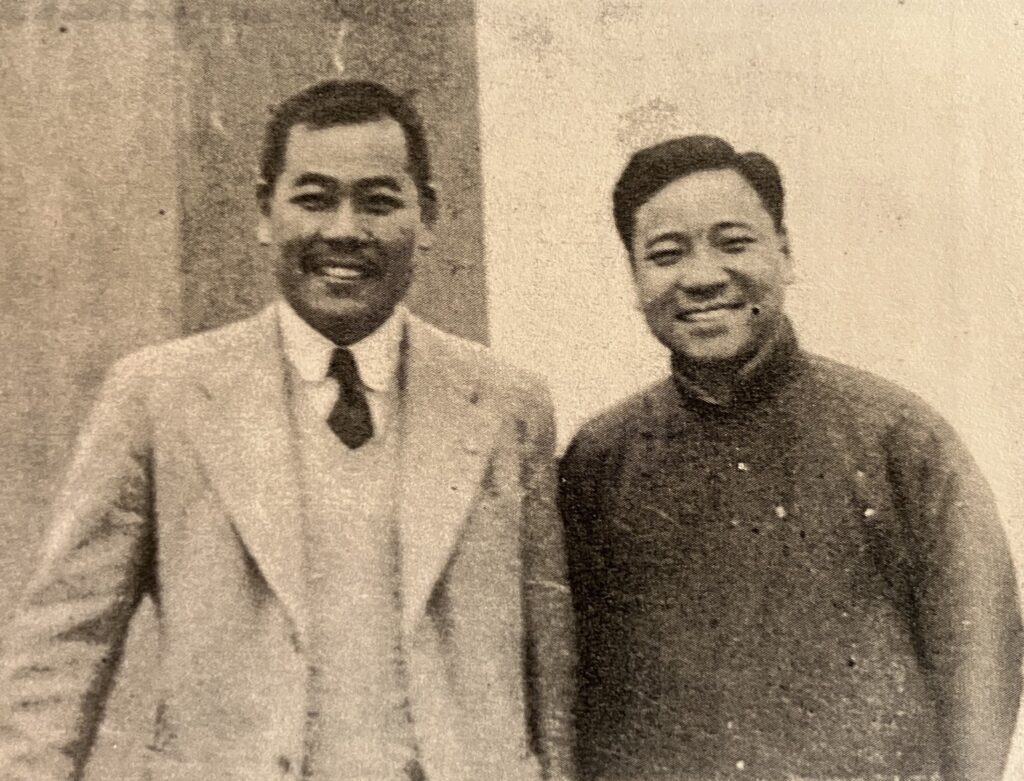

Outre ces activités de renseignement, Kawai Tatsuo, puis son remplaçant Ashino Hiroshi 蘆野弘 (1893-1985), confient également à Iwai le rôle de porte-parole de la légation auprès des journalistes chinois. Il devient ainsi l’un des principaux acteurs de la propagande internationale japonaise, relayée à Shanghai à la fois par des fonctionnaires comme Iwai et des journalistes tels que Matsumoto Shigeharu, dont il devient proche. C’est à cette époque qu’Iwai fait connaissance de Yuan Shu, un jeune journaliste qu’il sait être un agent du GMD. Bien qu’il lui connaisse des liens avec les Communistes, il ignore toutefois que Yuan est, en fait, un agent double du PCC recruté par Pan Hannian 潘漢年 (1906-1977). Lorsque Yuan Shu est arrêté en juin 1935 par les autorités de Shanghai en raison de ses liens avec les services secrets soviétiques, Iwai se démène pour le faire libérer. Il a l’idée d’utiliser un incident récent pour exercer un chantage sur le maire de Shanghai Wu Tiecheng 吳鐵城 (1888-1953), par l’intermédiaire d’un ancien soutien de Sun Yat-sen, Yamada Junsaburō 山田純三郎 (1876-1960). Le 3 mai 1935, les rédacteurs en chefs de deux journaux pro-japonais, Hu Enbo 胡恩薄 (?-1935) du Guoquanbao 國權報 et Bai Yuhuan 白逾桓 (1876-1935) du Zhenbao 振報, ont été assassinés dans la concession japonaise de Tianjin. Ce double attentat, attribué par les Japonais aux “chemises bleues” de Jiang Jieshi, sert de prétexte à l’Incident du Hebei (Hebei shijian 河北事件) qui aboutit, le 10 juin, à l’Accord He-Umezu (He-Mei xieding 何梅協定). En laissant entendre à Wu Tiecheng que l’arrestation de Yuan Shu sera perçu comme une nouvelle attaque contre un journaliste proche du Japon, Iwai obtient la libération immédiate de Yuan. Un lien de confiance indéfectible se noue alors entre les deux hommes, qui se prolongera sous l’occupation. Un dernier épisode, avant-guerre, marque durablement Iwai, au point qu’il lui consacrera une partie spécifique de ses mémoires. En août 1936, il se rend à Chengdu avec des agents de la police consulaire et des journalistes japonais pour rouvrir de force le consulat fermé suite à l’invasion de la Mandchourie. L'”Incident de Chengdu” (Rong’an 蓉案) donne lieu à des émeutes qui font deux morts parmi les journalistes japonais et plusieurs blessés, obligeant Iwai à renoncer à sa mission.

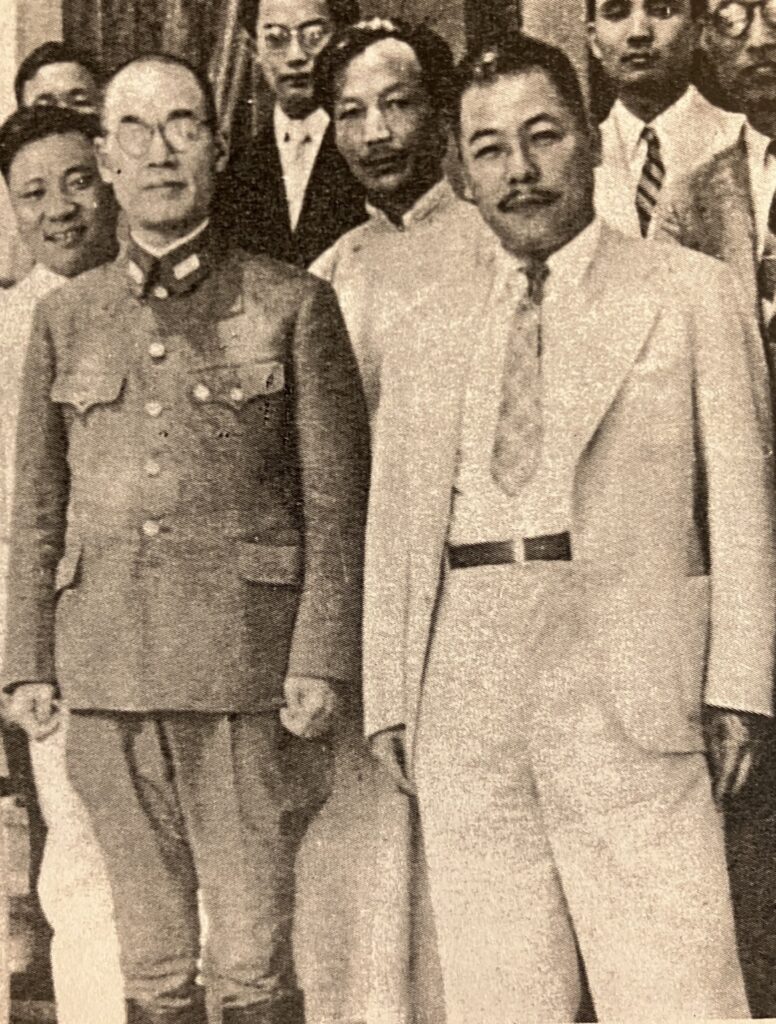

En août 1937, au lendemain de l’invasion japonaise, Iwai effectue à la demande de Kawai Tatsuo une mission d’observation de deux mois à Tianjin et Pékin, où il s’entretient notamment avec Doihara Kenji et Yazaki Kanjū. Il rencontre également Chen Zhongfu, dont il avait fait la connaissance avant-guerre grâce à Yamada Junzaburō. Chen lui présente l’ancien premier ministre Tang Shaoyi 唐紹儀 (1862-1938), alors courtisé par l’occupant pour prendre la tête d’un gouvernement collaborateur. En novembre 1937, Kagesa propose à Iwai de le recommander pour prendre la tête des affaires étrangères au sein du Conseil autonome anticommuniste du Hebei oriental (Jidong fangong zizhi weiyuanhui 冀東反共自治委員會) de Yin Rugeng, alors détenu par les troupes d’occupation après la mutinerie de Tongzhou. Iwai préfère retourner à Shanghai en décembre, cette fois comme vice-consul (fuku ryōji 副領事), poste prestigieux pour un homme issu comme lui du “petit concours” des Affaires étrangères qu’il a obtenu grâce à l’appui de Kawai. Il accompagne alors ce dernier pour une tournée dans la région du bas-Yangzi, où les forces d’occupation préparent la mise en place du Gouvernement réformé (weixin zhengfu 維新政府). À cette occasion, Iwai joue un rôle dans le choix du futur dirigeant du régime collaborateur. Deux officiers japonais, Chō Isamu 長勇 (1895-1945) et Usuda Kanzō 臼田寛三 (1891-1956), cherchent alors à faire nommer Wang Zihui 王子惠 (1892-?) président du Yuan exécutif (xingzheng yuanzhang 行政院長) du nouveau régime. Iwai reconnaît en lui l’homme qu’il connaissait sous le nom de Wang Huizhi 王晦知, du temps où il collectait des renseignements dans le Shanghai d’avant-guerre. Cette révélation vaut à Wang d’être remplacé par Liang Hongzhi et rétrogradé au rang de ministre de l’Industrie (shiye buzhang 事業部長) ; poste qu’il devait quitter dès août 1939 pour devenir l’un des émissaires de Kong Xiangxi dans les tentatives de négociations secrètes entre Chongqing et Tokyo.

Kawai Tatsuo ayant pris la tête des services de renseignement du Gaimushō en 1938, il confie à Iwai la Chine centrale, région clé en raison de la concentration d’agents chinois dans les concessions étrangères de Shanghai. Au-delà de la collecte d’informations, cette unité poursuit un objectif diplomatique : parvenir à une désescalade du conflit après l’échec de la médiation allemande et le discours anti-GMD du premier ministre Konoe Fumimaro le 16 janvier 1938. Depuis le début de la guerre, Kawai s’emploie en effet à défendre la désescalade aux côtés de son collègue Ishii Itarō, allant jusqu’à organiser à son domicile une rencontre secrète entre ce dernier et Ishiwara Kanji le 13 juillet 1937. L’action d’Iwai en Chine est également activement soutenue à Tokyo par la jeune garde du Gaimushō menée notamment par Takase Jirō 高瀬侍郎 (1906-1992). Simple employé de la 3e section du Bureau de l’information, Takase tire son influence de ses liens familiaux avec son beau-père Suzuki Kisaburō 鈴木喜三郎 (1867–1940), ancien ministre de la Justice et chef du Rikken seiyū-kai 立憲政友会. Takase est favorable à une politique expansionniste alignée sur l’Allemagne à la suite de Shiratori Toshio 白鳥敏夫 (1887-1949). Iwai obtient ainsi des fonds importants (et en partie secrets) du Gaimushō, puis, à partir de la seconde moitié de l’année 1940, du Bureau de liaison en Chine centrale du Kōa-in (Kōa-in Kachū renraku-bu 興亜院華中連絡部), pour collecter et analyser les informations sur la Chine libre dans le cadre d’une Unité d’enquête spéciale (tokubetsu chōsa-han 特別調査班) créée en avril 1938.

Communément appelée “Résidence d’Iwai” (Iwai kōkan 岩井公館), l’organisme installe ses bureaux dans un hôtel plutôt qu’au Consulat-général. Il relève en effet directement du Bureau de l’information à Tokyo, au grand dam des supérieurs directs d’Iwai en Chine. Outre des collègues comme Kimura Kakuzen 木村覚善, rencontré au moment de l’Incident de Hankou en avril 1927, Iwai s’entoure d’experts japonais de la Chine, tels que Kariya Kyūtarō 刈屋久太郎 (1910-?), auteur de travaux sur le secteur agricole en Chine central pour le compte du Bureau de recherche de la Mantetsu (Mantetsu chōsabu 満鉄調査部), ou encore Kajiwara Katsusaburō 梶原勝三郎, ancien journaliste au Shanhai mainichi shinbun 上海毎日新聞, passé par le Département de recherche économique sur l’Asie orientale (Tōa keizai chōsakyoku 東亜経済調査局), branche tokyoïte du Bureau de recherche de la Mantetsu dirigée par le célèbre Ōkawa Shūmei 大川周明 (1886-1957). Ils sont rejoints par une dizaine de jeunes fraîchement diplômés des meilleurs établissements de l’archipel, notamment du département de chinois de l’Université coloniale (takushoku daigaku 拓殖大学), ainsi que par plusieurs étudiants du Tōa dōbun shoin, tels que Koizumi Kiyukazu 小泉清一. Beaucoup de ces derniers accompagnent alors les troupes d’occupation comme interprètes (jūgun tsūyaku 従軍通訳), alors même que l’opposition au militarisme nippon en Chine est répandu parmi les élèves du “Shoin”. Resté proche de son alma mater, Iwai y trouve un large vivier de Japonais sinisants dans lequel il puise chaque année pour étoffer les rangs de son Unité d’enquête spéciale. Il aide ainsi son ancienne école à être élevée au statut d’université sur ordonnance impériale le 26 décembre 1939. Un de ses plus proches camarades de promotion, Chihara Kusuzō 千原楠蔵, recruté par le Asahi shinbun à sa sortie du Shoin, vient également prêter main forte. Cette bonne connaissance du chinois est indispensable pour la collecte d’informations qui passe notamment par la traduction de nombreux articles publiés dans la presse en Chine libre (Chongqing, Chengdu, Kunming, Gansu ou encore Xinjiang), ainsi que de documents confidentiels sur la situation politique, militaire et économique du camp adverse. Les renseignements tirés de ce travail de traduction sont ensuite transmis à l’ambassade et au consulat-général, ainsi qu’aux autorités locales de l’Armée de terre et de la Marine. Ils circulent sous le nom de code “101 jōhō 一〇一情報”, dont la prononciation est proche du nom d’Iwai ; raison pour laquelle, certaines sources parlent de la “101 Intelligence Organization”. La production de l’Unité est également diffusée sous forme de recueils imprimés : le Tsūjin 通訊 (Bulletin d’informations) publié tous les dix jours et le Tokuchōhan geppō 特調班月報 (Mensuel de l’Unité d’enquête spéciale). L’Unité publie, par ailleurs, un grand nombre de rapports fouillés sur toutes sortes de sujets (le système éducatif en zone libre, les syndicats ouvriers, le système du fermage au Sichuan, la situation locale au Shaanxi, etc.). En tout, près de 70 personnes, sans compter les dactylographes et le petit personnel, travaillent pour l’Unité d’enquête spéciale durant ses sept années d’existence.

Côté chinois, le principal bras droit d’Iwai est Yuan Shu, qui a pris l’initiative de le contacter peu avant et dont la loyauté redouble après qu’Iwai l’a – une nouvelle fois – sauvé des griffes de la police secrète de Li Shiqun à l’été 1939. Yuan lui présente Pan Hannian, qui se fait alors appeler “Hu 胡” – un pseudonyme dont Iwai se demande dans ses mémoires s’il fait volontairement écho à celui de “Hu Fu 胡服” utilisé par Liu Shaoqi durant une mission en zone nationaliste dans le Nord de la Chine en 1934. Iwai accepte de financer le périodique Ershi shiji 二十世紀 (Vingtième siècle) lancé par Pan à Hong Kong, en échange de renseignements. Recueillis et sélectionnés par les agents communistes de la colonie britannique, ces renseignements portent sur la situation politique en Chine libre ou encore les relations entre le gouvernement chinois et diverses puissances occidentales. Certaines de ces informations se révèlent précieuses, comme lorsque Pan apprend à Iwai que la personne se faisant passer pour Song Ziliang 宋子良 (1899-1983), beau-frère de Jiang Jieshi, dans l’”Opération Kiri” (Kiri kōsaku 桐工作) menée par Imai Takeo, est en fait un agent de Dai Li. Iwai s’empresse de faire remonter l’information à Abe Nobuyuki, qui la transmet à Itagaki Seishirō. Le soutien d’Iwai permet à Pan Hannian de développer un vaste réseau d’espionnage à Hong Kong et Shanghai pour le compte de Yan’an. Lorsque Hong Kong tombe aux mains des Japonais en décembre 1941, Iwai aide Pan à exfiltrer ses agents vers la zone libre et Shanghai.

À l’été 1938, Iwai se rend à Hong Kong où il retrouve son vieil ami le journaliste Chen Binhe 陳彬龢 (1897-1970), dont il espère mettre à profit les liens dans les milieux politiques opposés à Jiang Jieshi. Jusqu’à sa venue à Shanghai pour diriger le Shenbao 申報 en 1942, Chen devient ainsi l’un des principaux relais d’Iwai dans la collecte d’informations sur le régime de Chongqing. Iwai fait, par la suite, des allers-retours réguliers entre Shanghai et Hong Kong où il cumule des fonctions au consulat-général. Il se trouve ainsi dans la colonie britannique au moment de la défection de Wang Jingwei en décembre 1938. En avril 1939, lorsque ce dernier est exfiltré de Hanoï à la suite de l’assassinat de Zeng Zhongming, il est prévu qu’il fasse escale à Hong Kong, où Iwai est chargé d’organiser sa sécurité. Pour ce faire, il se rend à Tokyo pour recruter Kodama Yoshio 児玉誉士夫 (1911-1984), mafieux notoire frayant avec les milieux ultranationalistes, qui lui a été recommandé par Kawai Tatsuo. Wang fait finalement route directement vers Shanghai. Kodama l’y rejoint avec des armes et une dizaine d’hommes fournis par le lieutenant-colonel Usui Shigeki 臼井茂樹 (1898-1941), nouveau chef de la “section des stratagèmes” (bōryaku-ka 謀略課) fondée en novembre 1937 par Kagesa Sadaaki. À défaut de servir pour le groupe de Wang Jingwei, qui préfère ne pas dépendre des Japonais pour assurer sa sécurité, ces armes sont remises à l’Unité d’enquête spéciale d’Iwai, dont le service de sécurité est dès lors dirigé par le bras droit de Kodama, Iwada Yukio 岩田幸雄.

Alors que débutent les préparatifs en vue de la formation du Gouvernement national réorganisé, Iwai met sur pied en septembre 1939 un « Mouvement pour l’essor de l’Asie et la reconstruction nationale » (xingya jianguo yundong 興亞建國運動) à la demande de son ami Kagesa Sadaaki. Celui-ci cherche alors à faciliter la transition vers le nouveau gouvernement central en créant un front uni des collaborateurs et, plus largement, à gagner le soutien de la population. Son objectif est de former un véritable parti politique rassemblant l’ensemble des forces favorables à la paix (comprendre : pro-japonaises) au-delà du seul GMD “orthodoxe” de Wang Jingwei fondé en août 1939. Grâce à l’entregent de Yuan Shu et au soutien financier du Bureau de l’information – Kawai Tatsuo est soucieux de garder le contrôle face aux militaires, Iwai lance une vaste opération de séduction dans les milieux de la presse et de la culture. La direction du Mouvement pour l’essor de l’Asie et la reconstruction nationale est confiée à Yuan Shu, placé à la tête d’un comité directeur pour le moins bigarré. Il compte plusieurs agents secrets du PCC : Weng Yongqing 翁永清 (pseudonyme de Weng Congliu 翁從六), qui prend la direction de l’un des journaux du mouvement, le Xin Zhongguo bao 新中國報 (Journal de la Chine nouvelle) ; Liu Muqing 劉慕清 (également connu sous son nom de plume Lu Feng 魯風), qui devient le rédacteur en chef du même quotidien, et Chen Fumu. Ils y côtoient Tang Xun 唐巽, membre de la Clique C.C, Wang Haoran 汪浩然 de la Bande rouge (hongbang 洪幫), le professeur d’université Wang Fuquan 汪馥泉, et Zhou Bogan 周伯甘, ancien commandant dans l’Armée du Yunnan. On y trouve, enfin, des personnalités plus connues telles que le romancier à succès Zhang Ziping 張資平 (1893-1959) et Peng Ximing 彭羲明, ancien vice-ministre de la Justice (sifabu cizhang 司法部次長) sous le Gouvernement Beiyang. L’organisation se présente comme une initiative chinoise, dans laquelle Iwai et ses hommes ne participent qu’en tant que “conseillers” (guwen 顧問).

Afin de gérer l’afflux de membres issus des milieux étudiants, ouvriers ou encore de la pègre (Bande rouge et Bande verte), le mouvement se structure en plusieurs branches : Comité des jeunes (qingnian weiyuanhui 青年委員會), Comité des travailleurs (laodong weiyuanhui 勞動委員會), Comité de la culture (wenhua weiyuanhui 文化委員會), etc. En novembre 1939, Yuan Shu évalue ses effectifs à plus de 400 000 personnes, soit bien plus que la principale organisation de masse de Chine centrale, la Daminhui 大民會 (Association du grand peuple) mise en place par le Gouvernement réformé, qui compte jusqu’à 150 000 membres, sans parler du GMD “orthodoxe” de Wang Jingwei qui peine à recruter des délégués lors de sa fondation trois mois plus tôt. Entre le 26 novembre et le 12 décembre 1939, Iwai se rend à Tokyo avec huit dirigeants du Mouvement pour l’essor de l’Asie et la reconstruction nationale, afin de recevoir la bénédiction du gouvernement japonais. À son retour à Shanghai, il est cueilli à froid par Kagesa, qui lui demande d’annuler le lancement du Mouvement au motif qu’il fait de la concurrence au « Mouvement pour la paix et la reconstruction nationale » (heping jianguo yundong 和平建國運動) de Wang Jingwei. Craignant qu’il ne fasse de l’ombre à son propre Parti nationaliste, ce dernier exige que l’organisation d’Iwai se limite à des activités culturelles. Zhou Fohai, en particulier, fait courir le bruit qu’Iwai est un ancien membre du Parti communiste japonais. Malgré cette pression croissante, Iwai fait la sourde oreille. Dans ses mémoires, il affirme que son obstination excède à tel point les autorités militaire de Chine centrale que le colonel Yahagi Nakao 谷萩那雄 (1895-1949) aurait demandé à Kagesa l’autorisation de pouvoir l’éliminer.

Face à la menace de voir son organisation purement et simplement dissoute, Iwai se résout en février 1940 à recentrer son activité sur le domaine intellectuel. Il est prévu qu’elle se mette au service du futur gouvernement de Wang Jingwei dans la guerre culturelle que livre ce dernier contre Chongqing et Yan’an. Le Mouvement pour l’essor de l’Asie et la reconstruction nationale diffuse ses idées grâce à plusieurs périodiques en chinois. Il dispose déjà à l’époque d’un mensuel, le Xingjian 興建 (Essor et construction), auquel vient alors s’ajouter le quotidien Xin Zhongguo bao 新中國報 (Journal de la Chine nouvelle). Iwai équipe son journal de rotatives achetées au Asahi shinbun, grâce notamment à ses liens avec le vice-rédacteur en chef du quotidien, Ōnishi Itsuki 大西斎 (1887-1947), lui aussi un ancien du Tōa dōbun shoin. Échaudé par la volte face de Kagesa, Iwai cherche à s’assurer que l’armée ne lui mettra plus de bâtons dans les roues en se rapprochant de l’influent commandant Tsuji Masanobu, alors très impliqué dans la mobilisation des esprits en zone occupée. Trop occupé à Shanghai pour se rendre au quartier-général de l’Armée expéditionnaire de Chine (Shina hakengun 支那派遣軍) à Nankin, Iwai se fait représenter par Kodama Yoshio. Tsuji lui apporte un soutien enthousiaste et veut même confier à Iwai le poste de conseiller suprême (saikō komon 最高顧問) de la Daminhui 大民會 (Association du grand peuple), à la place du général de brigade Matsumuro Takayoshi 松室孝良 (1886-1969) qu’il juge inefficace. Iwai accepte pour des raisons financières notamment, comme il le reconnaît dans ses mémoires. Toutefois, Matsumuro refuse de céder sa place, obligeant Iwai à cohabiter avec lui à partir de sa prise de fonction en avril 1940 jusqu’à la dissolution de la Daminhui à l’hiver suivant.

Il s’efforce, par ailleurs, d’améliorer ses relations avec le principal adversaire de son mouvement au sein du nouveau gouvernement : Zhou Fohai. Ce dernier a, lui aussi, conscience qu’il devra composer avec Iwai. Le 3 juin 1940, à l’issue de ce qui semble être leur première rencontre, Zhou écrit dans son journal : “Mieux vaut s’en faire un ami, qu’un ennemi“. De son côté, Iwai envisage, sur les conseils de Yuan Shu, d’offrir à Zhou un poste de directeur général honoraire des publications du Mouvement. Cette bonne entente se traduit par une aide financière que Zhou, ministre des Finances, accorde au Mouvement pour l’essor de l’Asie et la reconstruction nationale. Le 18 juillet 1940, après avoir promis un versement mensuel de 30 000 yuans à l’organisation d’Iwai, Zhou note : “Au moins, ce groupe ne risque pas, dorénavant, de s’opposer à nous“. Si cette méthode consistant à acheter la loyauté des forces extérieures au groupe de Wang Jingwei a fait ses preuves, elle ne semble pas porter ses fruits dans le cas d’Iwai et de Yuan Shu. À la suite d’une visite de ce dernier, le 11 août 1940, Zhou laisse éclater sa colère : “ils prétendent vouloir être dirigés par le gouvernement, mais se tiennent en marge du GMD. Ils affirment, qui plus est, vouloir se placer sous mon patronage. Je crains toutefois qu’ils ne cherchent qu’à profiter de moi pour un temps, car cette organisation est utilisée par les Japonais pour entraver le GMD“. Zhou n’en continue pas moins à vouloir les “enrôler [wangluo 網羅]”, comme il l’écrit après une rencontre avec Iwai le 22 septembre 1940. Il arrive à ses fins le 17 décembre 1940, lorsque le Mouvement pour l’essor de l’Asie et la reconstruction nationale annonce sa dissolution.

Cette dissolution se fait dans le cadre de la création de la branche chinoise du Mouvement de la Ligue d’Asie orientale (Dongya lianmeng yundong 東亞聯盟運動) lancé par Ishiwara Kanji. En effet, pour mieux promouvoir le mouvement d’Ishiwara en Chine, son disciple Tsuji Masanobu propose comme contrepartie à Wang Jingwei d’obtenir des organisations de masse mises en place précédemment à Pékin (Xinminhui 新民會), Nankin (Daminhui), Wuhan (Parti républicain de He Peirong) et Shanghai (le Mouvement d’Iwai) qu’elles fusionnent dans l’Association générale chinoise de la Ligue d’Asie orientale (Dongya lianmeng Zhongguo zonghui 東亞聯盟中國總會) dirigée par Wang Jingwei. Alors que la Xinminhui parvient à contourner l’ordre de dissolution grâce à l’intervention du ministre de l’Armée Tōjō Hideki, l’organisation d’Iwai n’y échappe pas. Depuis le milieu de l’année 1940, en effet, elle dépend financièrement non plus du Gaimushō mais du Kōa-in, lui-même largement contrôlé par l’Armée de terre. Impuissant face aux militaires, Iwai est partagé entre la colère et la honte de ne pas avoir pu empêcher que ne partent en fumée les efforts des collaborateurs chinois qu’il a recrutés. Il en conçoit sans doute également un certain ressentiment contre le groupe de Wang Jingwei qu’il n’épargne pas de ses critiques par la suite. Si le Mouvement pour l’essor de l’Asie et la reconstruction nationale disparaît à la fin de l’année 1940, l’influence d’Iwai et des cadres de son organisation survit à cette disparition, à commencer par celle de son bras droit Yuan Shu, qui intègre les instances centrales du gouvernement de Nankin et, quelques mois plus tard, l’administration de la Campagne de pacification rurale (qingxiang gongzuo 清鄉工作) dirigée depuis Suzhou par Li Shiqun.

De fait, Iwai demeure une épine dans le pied du Gouvernement national réorganisé, grâce notamment au pouvoir de nuisance que lui confère son groupe de presse. Outre les titres déjà mentionnés, Iwai et Yuan Shu publient la revue Xianzheng yuekan 憲政月刊 (Mensuel du gouvernement constitutionnel), rebaptisée Zhengzhi yuekan 政治月刊 (Mensuel politique) en janvier 1941, lorsque le projet constitutionnel de Nankin est abandonné. Cette trahison de la promesse faite en mars 1940 alimente les articles critiques de collaborateurs proches d’Iwai, parmi lesquels plusieurs agents doubles communistes comme Yuan Shu et Chen Fumu. Un long article d’Iwai en particulier déclenche un tollé. Publié en mars 1942 dans Zhengzhi yuekan, il est intitulé “Guomin zhengfu de qianghua yu xin guomin yundong 國民政府的強化與新國民運動” (Le renforcement du gouvernement national et le Mouvement des nouveaux citoyens). Iwai n’y ménage pas ses coups contre le régime de Nankin et son GMD “orthodoxe”, allant même jusqu’à attaquer Wang Jingwei en personne : “Au moment du retour à la capitale, le Gouvernement national a pris l’apparence d’une coopération comprenant les différents partis et mouvances ainsi que les personnalités hors-partis. Par la suite, toutefois, ce gouvernement a malheureusement mis en œuvre une politique consistant à exercer un contrôle centralisé. […] Le centralisme du GMD s’est progressivement affirmé, connaissant un tournant avec la mise en place du Mouvement de la Ligue d’Asie orientale, et aboutissant, de fait, à une quasi dictature du GMD. […] Après la dissolution des différents partis et mouvances, le GMD a fait exactement la même chose que l’ancien GMD. Des luttes intestines l’ont divisé, des partis dans le Parti se sont formés et les malversations se sont multipliées […] La position du président Wang se détache progressivement et fait l’objet d’un culte croissant“. Iwai s’en prend plus largement à l’”opportunisme égoïste” des fonctionnaires chinois, ainsi qu’à la “coutume consistant à s’élever dans la fonction publique pour s’enrichir” qui constituent, selon lui, un obstacle empêchant le gouvernement de Wang Jingwei d’obtenir un plein soutien du Japon et de “gagner le cœur du peuple“. Reprenant la thèse essentialiste sur le manque de cohésion des Chinois, Iwai affirme que l’”égoïsme est l’un des grands défauts de la nation chinoise“. Ces propos provoquent la fureur des dirigeants de Nankin, Zhou Fohai le premier, qui exigent et obtiennent des excuses de Kagesa et de l’ambassadeur Hidaka Shinrokurō, lequel convoque Iwai pour l’admonester. Loin de s’amender, Iwai se vante de cette remontrance dans un rapport envoyé à Tokyo en août, auquel il joint la version japonaise de l’article, dans le souci, écrit-il, d’améliorer une situation qu’il juge catastrophique.

Cet interventionnisme d’Iwai dans le champ politique de la zone occupée passe également par le Tairiku shinpō 大陸新報 (le Continental), principal quotidien en langue japonaise de la zone occupée qui publie régulièrement des articles critiques à l’égard de Nankin. Iwai connaît bien son directeur, Fuke Toshiichi 福家俊一 (1912-1987), qu’il a aidé au moment de la création du journal en janvier 1939, aux côtés des représentants de l’Armée de terre et de la Marine, Kagesa et le capitaine de frégate Higo 肥後. À la suite de l’occupation par les troupes japonaises des concessions étrangères à partir du 8 décembre 1941, Iwai s’active pour relancer deux des principaux titres de la presse shanghaienne : le Shenbao et le Xinwenbao 新聞報. Pour diriger la rédaction du premier, Iwai fait venir de Hong Kong son ami Chen Binhe, un journaliste chevronné ayant déjà effectué un passage au Shenbao en 1931. Avec l’appui de Kagesa, il obtient pour cela le feu vert du Bureau de la presse (hōdōbu 報道部) des autorités militaires de Shanghai. Faute de disposer de fonds suffisants, il finance le lancement du journal grâce à l’apport de Satomi Hajime 里見甫 (1893-1965), diplômé deux ans avant lui du Tōa dōbun shoin, dont il fait la connaissance grâce à Inoue Isoji 井上磯次, un “aventurier du continent” (tairiku rōnin 大陸浪人) proche des milieux d’extrême-droite. Iwai jure dans ses mémoires qu’il n’avait aucune idée que Satomi, protégé par Harada Kumakichi, était l’un des principaux maîtres d’oeuvre du trafic d’opium utilisé par l’armée japonaise pour financer l’occupation de la Chine. Satomi remet également un chèque d’un million de yen à Yuan Shu pour soutenir ses activités. Dans le même temps, Iwai aide le nouveau rédacteur en chef du Xinwenbao, l’ancien vice-ministre des finances Li Sihao 李思浩 (1882-1968), à relancer le quotidien après la fuite de ses journalistes en dépêchant Liu Muqing.

L’influence d’Iwai passe également par l’éducation, domaine dans lequel il s’était impliqué dès 1940 en finançant un séjour d’étude au Japon pour des jeunes sélectionnés parmi les enfants et frères des membres du Mouvement pour l’essor de l’Asie et la reconstruction nationale. À l’issue d’une année d’apprentissage du japonais, les meilleurs d’entre eux passent les concours d’entrée des universités japonaises. Cette ambition, chez Iwai, de préparer l’amitié sino-japonaise d’après-guerre en formant la jeunesse chinoise trouve un cadre institutionnel avec la création, en juin 1941, de l’Institut d’auto-renforcement (ziqiang xueyuan 自強學院), sorte de Tōa dōbun shoin destiné aux étudiants chinois, qui installe ses locaux dans l’arrondissement de Zhabei 閘北區, au nord de Shanghai. Dirigé par Yuan Shu, l’établissement est présenté par Iwai, dans son discours d’inauguration, comme devant perpétuer l’esprit du Mouvement pour l’essor de l’Asie et la reconstruction nationale en jouant à cet égard un rôle comparable à celui tenu par l’Académie militaire de Huangpu pour la révolution nationale chinoise. Dans les faits, il sert surtout à produire des supplétifs chinois de l’impérialisme nippon, quoiqu’un certain nombre d’entre eux aient rallié le PCC à la fin de la guerre.

Les étudiants vivent en permanence au sein de l’Institut qui prend en charge l’ensemble de leurs frais. Outre des cours de japonais, de “technique militaire” (junshi shuke 軍事術科) et des séances de gymnastique, le cursus comprend des enseignements sur l’Asie du Sud-Est et ses communautés de Chinois d’outre-mer. Dans le contexte de tensions croissantes avec les États-Unis qui débouche sur l’entrée en guerre en décembre 1941, l’Institut d’auto-renforcement prévoit en effet de former des agents chinois capables d’accompagner l'”avancée vers le Sud”, notamment grâce à leur maîtrises des langues régionales de Chine méridionale (cantonais et minnan). Des intervenants extérieurs donnent régulièrement des conférences, tels que le libraire Uchiyama Kanzō 内山完造 (1885-1959), figure centrale des cercles intellectuels sino-japonais d’avant-guerre à Shanghai. Enfin, sur le modèle du Tōa dōbun shoin, des voyages d’études sont organisés dans le Jiangsu, notamment à partir de 1944, lorsque Yuan Shu est nommé à la tête du Bureau de l’éducation (jiaoyuting 教育廳) du gouvernement provincial.

Les 31 étudiants de la première promotion font leur rentrée en août 1941 et sortent diplômés en juin 1942. Un certain nombre d’entre eux sont immédiatement embauchés par l’Unité d’enquête spéciale d’Iwai ou intègrent la rédaction du Xin Zhongguo bao. C’est, par exemple, le cas de Ding Wenzhi 丁文治 (1921-1997), qui devient après-guerre un journaliste en vue à Taiwan, notamment au sein du Lianhebao 聯合報 (United Daily News). D’autres rejoignent les équipes de travail (gongzuotuan 工作團) de la Campagne de pacification rurale dont Yuan Shu est l’un des principaux cadres. Enfin, plusieurs étudiants originaires de Canton, de Shantou ou de Xiamen participent à l’expansion de l’empire japonais dans le Sud, en diffusant la propagande panasiatiste auprès de la diaspora chinoise, notamment en Indochine comme dans le cas de Yang Zhaokun 楊兆錕, qui dirige après-guerre une agence de voyage hongkongaise à destination des touristes japonais. Une seconde promotion, comptant également 31 étudiants, sort diplômée en juin 1944 à l’issue d’un cursus de deux ans.

Iwai cherche également à peser dans le domaine économique. Suite à l’invasion de Hong Kong en décembre 1941, plusieurs grands patrons shanghaiens qui avaient trouvé refuge dans la colonie britannique au début de la guerre sont placés en résidence surveillée, avant d’être renvoyés à Shanghai. Iwai voit là l’occasion de les fédérer pour qu’ils contribuent à l’effort de guerre et au renforcement du régime de Wang Jingwei. Il consulte Chen Binhe qui est très bien introduit dans les milieux d’affaires et désireux de développer la philanthropie pour venir en aide à la population shanghaienne. Sous la menace des autorités japonaises et chinoises, plusieurs grands noms des milieux d’affaires shanghaiens acceptent de collaborer, notamment au sein de la structure organisée par Iwai, baptisée l’Association sino-japonaise de commerce et d’industrie de Shanghai (Shanhai nikka kōshō rengikai 上海日華工商聯誼会) : les “trois anciens” Wen Lanting 聞蘭亭 (1870-1948), Yuan Lüdeng 袁履登 (1878-1954) et Lin Kanghou 林康侯 (1875-1965), ainsi que le banquier Tang Shoumin 唐壽民 (1892-1974), Ye Fuxiao 葉扶霄 (1879- ?), Zhu Boquan 朱博泉 (1898-2001), Feng Bingnan 馮炳南, Shen Siliang 沈嗣良 (1896-1967), Xu Jianping 許建屏 (1889-?), Zhao Jinqing 趙晉卿, Fei Fuheng 斐復恆, le directeur du groupe pharmaceutique Xinyayao 新亞藥, Xu Guanqun 許冠群, le roi de la conserve Xiang Kangyuan 項康原 (1895-1968), ou encore le magnat du textile Guo Shun 郭順. Côté japonais, Iwai rallie à son projet les représentants en Chine des principaux conglomérats tels que les directeur des branches locales de Mitsui 三井, Komuro Takeo 小室健夫 (1891-1967), Mitsubishi 三菱, Takagaki Katsujirō 高垣勝次郎 (1893-1967), Sumitomo 住友, Tōji Shun’ya 田路舜哉 (1893-1961), ainsi que le patron des filatures du groupe Toyota (Toyoda bōshoku-sha 豊田紡織社), Nishikawa Akiji 西川秋次 (1881-1963). Il obtient également la participation des principaux organismes économiques et financiers impliqués dans l’État d’occupation tels que la Compagnie pour le développement de la Chine centrale (Naka Shina shinkō kabushiki gaisha 中支那振興株式会社), représentée par son directeur Takajima Kikujirō 高島菊次郎 (1875-1969) et son vice-directeur Ueba Tetsuzō 植場鉄三 (1894-1964), ainsi que la Yokohama Specie Bank (Yokohama shōkin ginkō 横浜正金銀行) représentée par Kawamura Nishirō 河村二四郎 et Kiuchi Nobutane 木内信胤 (1899-1993).

Parallèlement, Iwai continue à diriger l’Unité d’enquête spéciale dont l’activité redouble après le déclenchement de la Guerre du Pacifique en décembre 1941. Ses effectifs sont renforcés pour répondre à la demande de renseignements sur la zone libre, notamment à propos de la situation économique à Chongqing. Cependant, le manque de personnels compétents et les difficultés croissantes rencontrées dans la collecte d’informations transitant par Hong Kong après la venue de Chen Binhe à Shanghai empêchent l’Unité de jouer le rôle qu’ambitionne de lui donner Iwai. En novembre 1942, l’Unité passe sous l’autorité du ministère de la Grande Asie orientale (daitōashō 大東亜省). Nommé consul de Shanghai en janvier 1943, Iwai apprend en juillet sa mutation prochaine à Canton. Il est alors invité à Nankin pour rencontrer Wang Jingwei au cours d’un entretien d’une heure. En janvier 1944, il prend ses fonctions à Canton, où s’efforce d’emblée d’établir de bonnes relations avec le gouverneur Chen Chunpu. Un an plus tard, en janvier 1945, il accède au rang de consul de Canton.

Son mandat à Canton est toutefois interrompu par une mission prolongée à Macao. Le 3 février 1945, le consul japonais de la colonie portugaise, Fukui Yasumitsu 福井保光 (1902-1945) – lui aussi un ancien du Tōa dōbun shoin – est assassiné lors de sa séance matinale de gymnastique radiophonique. Iwai reçoit l’ordre d’assurer l’intérim tout en enquêtant sur la mort de son collègue. Rechignant à partir, il écrit à Tokyo pour être remplacé, arguant du fait que ses activités d’espionnage contre Chongqing font de lui une cible. Iwai arrive finalement le 19 mars 1945, entouré d’une garde rapprochée de dix hommes dirigés par un certain Sun Jiahua 孫嘉華, dont le nombre est multiplié par cinq dans les semaines qui suivent. Il porte en permanence une arme sur lui, ce dont s’étonne le gouverneur Gabriel Maurício Teixeira (1897-1973). Le contexte est d’autant plus tendu que le Japon vient de mener un violent coup de force contre les autorités coloniales françaises en Indochine. Si l’enclave portugaise s’efforce de rester neutre dans le conflit sino-japonais, l’armée japonaise fait peser sur elle une menace permanente depuis l’ultimatum transmis le 27 août 1941 par Fukui au moment de sa prise de fonction. L’attentat exacerbe également les tensions entre diplomates et militaires japonais. Le chef de la diplomatie, Shigemitsu Mamoru, parvient à éviter que l’attentat, que d’aucuns attribuent au chef de l’agence des services spéciaux locale, le colonel Sawa Eisaku 沢栄作 (-1947), ne serve de prétexte à une occupation japonaise de Macao, alors qu’un blocus économique est déjà imposé. Dans ce contexte, Iwai adopte une ligne dure consistant à exiger des autorités portugaises qu’elles présentent des excuses, arrêtent des suspects, payent une indemnité et promettent d’assurer la sécurité des ressortissants japonais. Ces conditions sont critiquées par l’ambassadeur du Japon à Lisbonne, Morishima Morito 森島守人 (1896-1975), qui considère qu’une indemnité n’a aucun sens et que le Japon devrait mettre un terme au blocus, démanteler les activités de renseignement de Sawa et nommer un consul parlant le portugais. Le 29 avril 1945, Iwai convie les principaux représentants de la communauté chinoise de Macao à un banquet pour l’anniversaire de l’empereur Shōwa au cours duquel il leur extorque une forte somme d’argent qui sert à compléter une trésorerie asséchée par l’inflation galopante. En effet, comme il le reconnaît dans ses mémoires, Iwai ne laisse guère le choix aux notables chinois qui sont prévenus que faute d’argent pour rémunérer sa garde de cinquante hommes de main chinois, il sera contraint de laisser ces derniers reprendre leurs activités de gangsters. En mai, il est remplacé par Yodagawa Masaki 淀川正樹, lusophone ayant occupé le poste de consul au Timor.

Fin juillet 1945, Iwai se rend à Tokyo pour remettre son rapport sur la situation à Macao. Lors de son escale à Nankin, il fait un détour par Shanghai pour s’entretenir avec Yuan Shu, lors de ce qui devait être la dernière rencontre entre les deux hommes. À Tokyo, Iwai retrouve sa femme et leurs trois filles qui ont vu leur logement entièrement détruit lors du dernier grand bombardement américain de la capitale, le 23 mai 1945. Peu après la défaite, Iwai est visé par un mandat d’arrêt du gouvernement chinois. En septembre 1945, il présente sa démission qui est acceptée en décembre après qu’il a été promu au rang de consul-général (sōryōji 総領事). Au lendemain de la guerre, Iwai est convaincu que la reconstruction de l’économie japonaise passera par le commerce avec la Chine. Aidé par deux anciens cadres de l’Unité d’enquête spéciale, Takei Tatsuo 武井竜男 et Takahashi Chūsaku 高橋忠作, il lance en 1949 une revue en chinois intitulée Xin Riben jingji maoyi yuebao 新日本經濟貿易月報 (Mensuel de l’économie et du commerce du nouveau Japon) qu’il finance difficilement en sollicitant ses relations. La traduction vers le chinois est assurée par d’anciens étudiants chinois partis en échange au Japon pendant la guerre à l’initiative d’Iwai, tels que Chen Dihua 陳棣華, diplômé en économie à l’Université Keiō 慶應大学, assisté par le fils de Zhang Ziping, passé par l’Université de médecine de Kanazawa 金沢医科大学. En dépit de la victoire communiste en Chine, le périodique continue à être acheté par des organismes économiques à Tianjin et Shanghai. L’essentiel de ses ventes se fait néanmoins à Hong Kong, où Iwai peut compter sur le soutien de son ancien secrétaire Sun Jiahua 孫嘉華, ainsi que dans les communautés de Chinois d’outre-mer en Asie du Sud-Est et même en Afrique. L’aventure éditoriale ne tarde toutefois pas à se heurter à la propagande communiste auprès de la communauté chinoise de l’archipel, privant Iwai de ses traducteurs qui décident de contribuer à la construction de la Nouvelle Chine. Zhang s’installe ainsi à Pékin, tandis que Chen Dihua part pour Wuhan.

Iwai est, par ailleurs, très impliqué dans les cercles issus de l’État d’occupation japonais en Chine. À la suite de la victoire communiste en 1949, une poignée d’anciens collaborateurs chinois, tels que Hu Lancheng, se sont installés au Japon où ils vivent dans des conditions souvent précaires. Leur situation devient plus inconfortable encore en 1952, après la fin de l’occupation américaine et la signature du Traité de San Francisco, lorsque le gouvernement de Yoshida Shigeru est mis sur la sellette par la gauche qui l’accuse de protéger les anciens collaborateurs de l’impérialisme nippon. Iwai cherche à leur venir en aide en remobilisant ses contacts au Gaimushō et dans les milieux d’affaires, notamment Takajima Kikujirō. Sous la houlette de Shimizu Tōzō, Iwai participe ainsi, en juin 1959, à l’organisation de l’Association de bon voisinage (zenrin yūgi-kai 善隣友誼会), baptisée en référence sans doute au premier des trois principes énoncés le 22 décembre 1938 par Konoe Fumimaro qui servent de base à la politique de collaboration. Cet organisme offrant une aide financière aux anciens collaborateurs chinois réfugiés dans l’archipel est présidé successivement par l’ancien ministre des Affaires étrangères Tani Masayuki 谷正之 (1889-1962), Hidaka Shinrokurō et, à la mort de ce dernier en 1976, par l’ancien vice-consul à Nankin et Shanghai au tournant des années 1930, Ōta Ichirō 太田一郎 (1902-1996). Son conseil d’administration est composé d’anciens dirigeants japonais impliqués dans l’État d’occupation issus de l’Armée de terre (Imai Takeo, Okamura Yasuji et Yazaki Kanjū), de la Marine (Tsuda Shizue 津田静枝, Teraoka Kinpei 寺岡謹平 et Kobettō Sōzō 小別当惣三 ) et du Gaimushō (Shimizu Tōzō et Iwai).

À partir du milieu des années 1970, Iwai met par écrit ses souvenirs qui paraissent en plusieurs parties, d’abord dans la revue Koyū 滬友 (Amis de Shanghai) publiée par des anciens du Tōa dōbun shoin, avant d’être réunis en 1983 sous le titre Kaisō no Shanghai 回想の上海 (Souvenirs de Shanghai). Il y revient principalement sur ses deux séjours prolongés à Shanghai avant et pendant la guerre. L’un de ses objectifs avoués est de rétablir la vérité sur ses activités en Chine occupée dont l’image a été faussée, selon lui, par la presse de gauche et, surtout, par les mémoires de Kodama Yoshio, connu après-guerre pour son rôle dans le vaste scandale de corruption lié à l’entreprise aérospatiale Lockheed. En août 1982, Iwai retourne en Chine pour la première fois dans le cadre d’un voyage organisé auquel participent des anciens du Tōa dōbun shoin. En mai 1983, il passe quelques jours à Hong Kong, puis à Taipei, où il retrouve d’ancien élèves de son Institut d’auto-renforcement.

Sources : NKJRJ, p. 71 ; Iwai 1983 ; Koizumi 2003 ; Yuan Shu 1984 ; Liu Jie 1996, p. 145 sqq. ; Seki 2012 ; Brooks 2000, p. 57, 76, 99, 183 ; NRSJ, p. 150, 161 ; Reynolds 1989, p. 267-268 ; Yang Tianshi 1997, p. 37-43 ; Xiao-Planes 2010, p. 129-130 ; MZN, p. 1028 ; JACAR B02030601400 ; AH 118-010100-0032-027 ; Horii 2011, p. 265 ; ZR, p. 304, 323, 334, 354 ; Gunn 2016, p. 33, 49-51, 156 ; Lo 2022, p. 159 ; Seki 2019, p. 453-475 ; Baidu.

The younger son of a merchant from Aichi who was adopted by another merchant family, Iwai Eiichi went to study in 1918 at the Tōa Dōbun Shoin 東亜同文書院 (East Asia Common Culture Academy), an institute established in 1900 to educate Japanese specialists on China, located in Shanghai. After graduating in 1921 from the commerce department (shōmuka 商務課) of the Shanghai institution, he joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (gaimushō 外務省) that same year as a simple interpreter. Iwai then embarked on a career during which he spent a total of nineteen years in China, compared to five years in Japan. Initially stationed in Chongqing, he was transferred to Shantou 汕頭 (Guangdong) in 1922, then returned to Japan in 1924, where he married and worked for the 1st section of the Information Bureau (jōhōbu dai ichi ka 情報部第一課) of his ministry. In 1926, he was sent to the consulate in Changsha (Hunan) as a chancellor (shokisei 書記生), a subordinate position reserved for consular staff, separate from the prestigious diplomatic corps, the majority of whom in China, like Iwai, were graduates of the Tōa Dōbun Shoin. As the Northern Expedition unfolded, accompanied by a rise in Chinese patriotism, Japanese residents became targets of the local population, particularly in Wuhan where the Hankou Incident (Hankō jiken 漢口事件) occurred on April 3, 1927, but also in Changsha. Between April and August, Iwai and his family took refuge in the Japanese concession of Hankou.

During this period, Iwai made a name for himself by publishing two essays in the journal Shina 支那 (China) published by the Association for East Asian Common Culture (Tōa Dōbun-kai 東亜同文会), the parent organization of the Tōa Dōbun Shoin. The first essay, “Shina kokusai kyōdō hogo-ron” 支那国際共同保護論 (On the International Joint Protection of China), appeared in June 1928, and contemplated a reversal of the imperialistic project of “international management of China” in favor of a more “friendly” approach. Iwai argued that it was the responsibility of Japan and other powers to assist the Chinese population by organizing a world summit driven by “humanist” values, which would send an international force to China tasked with restoring order. The second article, “Manshū mondai kaiketsu no kyakkanteki kōsatsu” 満洲問題解決の客観的考察 (Objective Considerations on the Resolution of the Manchurian Problem), was published in October 1929, on the eve of the 3rd summit of the Institute of Pacific Relations (Taiheiyō mondai chōsa-kai 太平洋問題調査会) in Kyoto, where the Manchurian question was hotly contested between Matsuoka Yōsuke 松岡洋右 (1880-1946) and the head of the Chinese delegation, Xu Shuxi 徐淑希 (1892-1982). In this article, Iwai advocated for a “diplomatic” solution aimed at preventing the escalation of tensions caused by the centralization policies of the National Government following the assassination of Zhang Zuolin, on one hand, and the expansionism of the Kwantung Army in Manchuria, on the other. Like other Japanese leaders at the time, he suggested that Japan should acquire Manchuria, which he believed rightfully belonged to Japan due to the great sacrifices it made in the victory over Russia in 1905. Reflecting on this stance in his memoirs published in 1983, Iwai even claimed that without this sacrifice, the Northeastern provinces would never have been part of the Chinese national territory as defined in 1945. This diplomatic path he defended in 1929 was swept aside by the “Mukden Incident” on September 18, 1931.

Following a two-year tenure in Tokyo at the Telecommunications Section (denshin-ka 電信課), a period during which he led a strike against salary cuts at the Gaimushō, Iwai returned to a tumultuous China. He arrived in Shanghai in February 1932, just days after the outbreak of hostilities that saw Chinese troops fiercely resisting the Japanese coup de force. With Japanese diplomacy isolated on the international and Chinese stages and lacking adequate means to gather intelligence on enemy countries, Iwai, with the support of Ambassador Shigemitsu Mamoru, proposed to the ministry’s leadership a plan to equip the Shanghai legation with an Information Bureau (jōhōbu 情報部). Under the direction of its chief, Suma Yakichirō 須磨弥吉郎 (1892-1970), Iwai obtained intelligence revealing the existence of a secret organization formed in support of Jiang Jieshi by officers from the Whampoa Military Academy, which would later become known as the “Blue Shirts” (lanyishe 藍衣社). In April 1942, he published a Chinese translation of this report – Lanyishe neimu 藍衣社內幕 (The Inner Workings of the Blue Shirts Society), which enjoyed great success in the occupied zone. Another notable achievement: during the diplomatic incident caused by the publication on May 4, 1935, of an article mocking Emperor Shōwa in the Shanghai magazine Xinsheng 新生 (New Life), Iwai was able to prove that the article in question had been authorized by the Censorship Committee of the GMD’s Central Bureau and decided to relay this information to the deputy military attaché of the Japanese legation, Kagesa Sadaaki. The two men had met in August 1934 through the efforts of Kawai Tatsuo 河相達夫 (1889-1965), who had replaced Suga in November 1933 as the head of the Information Bureau. Convinced that he had a golden opportunity to force the KMT to stop its anti-Japanese propaganda, Iwai sought to bypass his own superiors, who were concerned that this incident could threaten Sino-Japanese détente. Through Kagesa, he managed to have the army put pressure on the nationalist regime, leading to the Central Bureau’s Secretary-General Ye Chucang 葉楚傖 issuing a written apology.

In addition to intelligence activities, Kawai Tatsuo, followed by his successor Ashino Hiroshi 蘆野弘 (1893-1985), also entrusted Iwai with the role of spokesman for the legation to the Chinese press. He thus became one of the main agents of Japanese international propaganda in Shanghai, disseminated both by officials like Iwai and journalists such as Matsumoto Shigeharu, with whom he became close. It was during this time that Iwai met Yuan Shu, a young journalist he knew to be an agent of the GMD. Although aware of Yuan’s connections to the Communists, Iwai was unaware that Yuan was, in fact, a double agent for the CCP recruited by Pan Hannian 潘漢年 (1906-1977). When Yuan Shu was arrested in June 1935 by the Shanghai authorities because of his ties with the Soviet secret services, Iwai worked tirelessly for his release. He conceived the idea of using a recent incident to blackmail the Mayor of Shanghai, Wu Tiecheng 吳鐵城 (1888-1953), through an old supporter of Sun Yat-sen, Yamada Junsaburō 山田純三郎 (1876-1960). On May 3, 1935, the editors-in-chief of two pro-Japanese newspapers, Hu Enbo 胡恩薄 (?-1935) of the Guoquanbao 國權報 and Bai Yuhuan 白逾桓 (1876-1935) of the Zhenbao 振報, had been assassinated in the Japanese concession in Tianjin. This double assassination, attributed by the Japanese to Jiang Jieshi‘s “Blue Shirts,” served as a pretext for the Hebei Incident (Hebei shijian 河北事件), which culminated on June 10 in the He-Umezu Agreement (He-Mei xieding 何梅協定). By implying to Wu Tiecheng that Yuan Shu‘s arrest would be perceived as a new attack against a journalist close to Japan, Iwai secured Yuan‘s immediate release. A strong bond of trust was forged between the two men, which continued throughout the occupation. One last pre-war episode left a lasting impression on Iwai, to the point of dedicating a specific part of his memoirs to it. In August 1936, he went to Chengdu with consular police agents and Japanese journalists to forcibly reopen the consulate that had been closed following the invasion of Manchuria. The “Chengdu Incident” (Rong’an 蓉案) led to riots that resulted in the deaths of two Japanese journalists and several injuries, forcing Iwai to abandon his mission.

In August 1937, following the Japanese invasion, Iwai, upon the request of Kawai Tatsuo, undertook a two-month observational mission to Tianjin and Beijing, where he held discussions with Doihara Kenji and Yazaki Kanjū. He also met with Chen Zhongfu, whom he had gotten to know before the war through Yamada Junzaburō. Chen introduced him to the former Prime Minister Tang Shaoyi 唐紹儀 (1862-1938), who was being courted by the occupiers to lead a collaborationist government. In November 1937, Kagesa offered to recommend Iwai to head the foreign affairs department within the Eastern Hebei Anti-Communist Autonomous Council (Jidong fangong zizhi weiyuanhui 冀東反共自治委員會) of Yin Rugeng, who was then detained by the occupying troops after the Tongzhou mutiny. Iwai preferred to return to Shanghai in December, this time as Deputy Consul (fuku ryōji 副領事), a prestigious position for a man who, like him, had been recruited through the “small examination”. He secured this position with the support of Kawai. Iwai then accompanied the latter on a tour of the lower Yangtze region, where the occupation forces were preparing to establish the Reformed Government (weixin zhengfu 維新政府). On this occasion, Iwai played a role in selecting the future leader of the collaborative regime. Two Japanese officers, Chō Isamu 長勇 (1895-1945) and Usuda Kanzō 臼田寛三 (1891-1956), were then seeking to appoint Wang Zihui 王子惠 (1892-?) as the president of the Executive Yuan (xingzheng yuanzhang 行政院長) of the new regime. Iwai recognized in him the man he knew as Wang Huizhi 王晦知 from when he was collecting intelligence in pre-war Shanghai. This revelation led to Wang being replaced by Liang Hongzhi and demoted to the position of Minister of Industry (shiye buzhang 事業部長), a post he would leave in August 1939 to become one of Kong Xiangxi‘s emissaries in the attempts at secret negotiations between Chongqing and Tokyo.

With Kawai Tatsuo as the new head of the Gaimushō’s intelligence services in 1938, Iwai was entrusted with Central China, a key region due to the concentration of Chinese agents in the foreign concessions of Shanghai. Beyond information gathering, this unit pursued a diplomatic objective: to achieve a de-escalation of the conflict following the failure of German mediation and the anti-GMD speech by Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro on January 16, 1938. Since the beginning of the war, Kawai had indeed been advocating for de-escalation alongside his colleague Ishii Itarō, even organizing a secret meeting at his home between the latter and Ishiwara Kanji on July 13, 1937. Iwai’s activities in China were also actively supported in Tokyo by the young guard of the Gaimushō, notably led by Takase Jirō 高瀬侍郎 (1906-1992). As a mere employee of the 3rd section of the Information Bureau, Takase drew his influence from his familial ties with his father-in-law Suzuki Kisaburō 鈴木喜三郎 (1867–1940), former Minister of Justice and leader of the Rikken seiyū-kai 立憲政友会. Takase favored an expansionist policy in line with Germany following Shiratori Toshio 白鳥敏夫 (1887-1949). Thus, Iwai obtained significant (and partly secret) funding from the Gaimushō, and later, from the second half of the year 1940, from the Central China Liaison Office of the Kōa-in (Kōa-in Kachū renraku-bu 興亜院華中連絡部), to collect and analyze information on Free China as part of a Special Investigation Unit (tokubetsu chōsa-han 特別調査班) established in April 1938.

Commonly referred to as the “Iwai Residence” (Iwai kōkan 岩井公館), the agency set up its offices in a hotel rather than the Consulate-General. Indeed, it reported directly to the Information Bureau in Tokyo, much to the chagrin of Iwai’s direct superiors in China. In addition to colleagues like Kimura Kakuzen 木村覚善, whom he met during the Hankou Incident in April 1927, Iwai surrounded himself with Japanese experts on China, such as Kariya Kyūtarō 刈屋久太郎 (1910-?), who authored studies on the agricultural sector in Central China for the Mantetsu Research Bureau (Mantetsu chōsabu 満鉄調査部), and Kajiwara Katsusaburō 梶原勝三郎, a former journalist at the Shanhai mainichi shinbun 上海毎日新聞, who had been through the East Asian Economic Research Department (Tōa keizai chōsakyoku 東亜経済調査局), the Tokyo branch of the Mantetsu Research Bureau led by the famous Ōkawa Shūmei 大川周明 (1886-1957). They were joined by about a dozen young graduates from the best institutions in Japan, notably from the Chinese department of the Colonial University (Takushoku daigaku 拓殖大学), as well as several students from the Tōa Dōbun Shoin, such as Koizumi Kiyukazu 小泉清一. Many of these were accompanying the occupation troops as interpreters (jūgun tsūyaku 従軍通訳), even though opposition to Japanese militarism in China was widespread among the “Shoin” students. Remaining close to his alma mater, Iwai found a large pool of Chinese speakers from which he drew each year to bolster the ranks of his Special Investigation Unit. He thus helped his former school to be elevated to the status of a university by imperial ordinance on December 26, 1939. One of his closest classmates, Chihara Kusuzō 千原楠蔵, recruited by the Asahi shinbun upon graduation from the Shoin, also came to lend a hand. This good knowledge of Chinese was indispensable for the collection of information, which included the translation of numerous articles published in the Free China press (Chongqing, Chengdu, Kunming, Gansu, or Xinjiang), as well as confidential documents on the political, military, and economic situation of the opposing side. The intelligence gleaned from this translation work was then transmitted to the embassy and the Consulate-General, as well as to the local authorities of the Army and Navy. They circulated under the code name “101 jōhō 一〇一情報”, whose pronunciation is close to the name of Iwai; for this reason, some sources refer to the “101 Intelligence Organization”. The Unit’s output was also distributed in the form of printed compendiums: the Tsūjin 通訊 (Information Bulletin) published every ten days and the Tokuchōhan geppō 特調班月報 (Special Investigation Unit Monthly). The Unit also published a large number of detailed reports on a variety of topics (the educational system in the free zone, workers’ unions, the tenant farming system in Sichuan, the local situation in Shaanxi, etc.). In total, nearly 70 people, not counting typists and support staff, worked for the Special Investigation Unit during its seven years of existence.

On the Chinese side, Iwai’s principal lieutenant was Yuan Shu, who had taken the initiative to contact him shortly before and whose loyalty increased after Iwai – once again – saved him from the clutches of Li Shiqun‘s secret police in the summer of 1939. Yuan introduced him to Pan Hannian, who was then going by the pseudonym “Hu 胡” – a name that Iwai wondered in his memoirs if it was intentionally echoing “Hu Fu 胡服,” used by Liu Shaoqi during a mission in the Nationalist zone in Northern China in 1934. Iwai agreed to fund the periodical Ershi shiji 二十世紀 (Twentieth Century) launched by Pan in Hong Kong, in exchange for intelligence. This intelligence, gathered and selected by Communist agents in the British colony, pertained to the political situation in Free China or the relationships between the Chinese government and various Western powers. Some of this information proved to be valuable, such as when Pan informed Iwai that the person impersonating Song Ziliang 宋子良 (1899-1983), Jiang Jieshi‘s brother-in-law, in the “Operation Kiri” (Kiri kōsaku 桐工作) conducted by Imai Takeo, was in fact an agent of Dai Li. Iwai quickly relayed the information to Abe Nobuyuki, who passed it on to Itagaki Seishirō. Iwai’s support allowed Pan Hannian to develop an extensive espionage network in Hong Kong and Shanghai on behalf of Yan’an. When Hong Kong fell to the Japanese in December 1941, Iwai helped Pan to exfiltrate his agents to the free zone and Shanghai.

In the summer of 1938, Iwai traveled to Hong Kong where he met his old friend, the journalist Chen Binhe 陳彬龢 (1897-1970), whose connections in political circles opposed to Jiang Jieshi he hoped to utilize. Until his move to Shanghai to lead the Shenbao 申報 in 1942, Chen became one of Iwai’s main conduits in gathering information on the Chongqing regime. Subsequently, Iwai regularly traveled between Shanghai and Hong Kong, where he also hold positions at the consulate-general. He was in the British colony when Wang Jingwei defected in December 1938. In April 1939, when Wang was smuggled out of Hanoi following the assassination of Zeng Zhongming, he was scheduled to stop in Hong Kong, where Iwai was tasked with organizing his security. To this end, he traveled to Tokyo to recruit Kodama Yoshio 児玉誉士夫 (1911-1984), a notorious gangster with ultranationalist ties, who had been recommended by Kawai Tatsuo. Wang ended up traveling directly to Shanghai. Kodama joined him there with weapons and a dozen men supplied by Lieutenant Colonel Usui Shigeki 臼井茂樹 (1898-1941), the new head of the “strategy section” (bōryaku-ka 謀略課) founded in November 1937 by Kagesa Sadaaki. Although these weapons were not used for Wang Jingwei‘s group, who preferred not to rely on the Japanese for security, they were handed over to Iwai’s Special Investigation Unit, whose security service was henceforth directed by Kodama’s right-hand man, Iwada Yukio 岩田幸雄.

As preparations for the formation of the Reorganized National Government began, Iwai set up in September 1939 a “Movement for the Rise of Asia and National Reconstruction” (Xingya jianguo yundong 興亞建國運動) at the request of his friend Kagesa Sadaaki. Kagesa was seeking to facilitate the transition to the new central government by creating a united front of collaborators and, more broadly, to garner the support of the population. His goal was to form a political party that would encompass all forces favorable to peace (i.e., pro-Japanese) beyond Wang Jingwei’s “orthodox” GMD founded in August 1939. Through the networking of Yuan Shu and the financial support of the Information Bureau – Kawai Tatsuo was eager to maintain control in the face of the military, Iwai launched a vast charm offensive in the press and cultural circles. The leadership of the Movement for the Rise of Asia and National Reconstruction was entrusted to Yuan Shu, who headed a rather diverse steering committee. It included several secret agents of the CCP: Weng Yongqing 翁永清 (pseudonym of Weng Congliu 翁從六), who took over the direction of one of the movement’s newspapers, the Xin Zhongguo bao 新中國報 (New China Newspaper); Liu Muqing 劉慕清 (also known by his pen name Lu Feng 魯風), who became the editor-in-chief of the same daily, and Chen Fumu. They rubbed shoulders with Tang Xun 唐巽, a member of the CC Clique, Wang Haoran 汪浩然 from the Red Gang (hongbang 洪幫), the university professor Wang Fuquan 汪馥泉, and Zhou Bogan 周伯甘, former commander in the Yunnan Army. Finally, there were more well-known personalities such as the successful novelist Zhang Ziping 張資平 (1893-1959) and Peng Ximing 彭羲明, former Vice Minister of Justice (sifabu cizhang 司法部次長) under the Beiyang Government. The organization presented itself as a Chinese initiative, in which Iwai and his men only participated as “advisors” (guwen 顧問).

To manage the influx of members from student circles, laborers, and the underworld (the Red and Green Gangs), the movement structured itself into several branches: the Youth Committee (qingnian weiyuanhui 青年委員會), the Workers’ Committee (laodong weiyuanhui 勞動委員會), the Culture Committee (wenhua weiyuanhui 文化委員會), among others. In November 1939, Yuan Shu estimated his membership at over 400,000 individuals, far exceeding the main mass organization in Central China, the Daminhui 大民會 (Great People’s Association), established by the Reformed Government, which had up to 150,000 members, not to mention the Wang Jingwei’s “orthodox” GMD which struggled to recruit delegates at its founding three months earlier. Between November 26 and December 12, 1939, Iwai traveled to Tokyo with eight leaders of the Movement for the Rise of Asia and National Reconstruction to receive the blessings of the Japanese government. Upon his return to Shanghai, he was coldly confronted by Kagesa, who demanded the cancellation of the Movement’s launch on the grounds that it competed with Wang Jingwei‘s “Movement for Peace and National Reconstruction” (heping jianguo yundong 和平建國運動). Fearing it might overshadow his own Nationalist Party, Wang insisted that Iwai’s organization be confined to cultural activities. Zhou Fohai, in particular, spread rumors that Iwai was a former member of the Japanese Communist Party. Despite this mounting pressure, Iwai turned a deaf ear. In his memoirs, he claims his obstinacy was such that Colonel Yahagi Nakao 谷萩那雄 (1895-1949) had asked Kagesa for permission to eliminate him.

Faced with the threat of having his organization completely dissolved, Iwai decided in February 1940 to refocus his activity on the intellectual domain. It was planned that his organization would serve the future government of Wang Jingwei in the cultural war waged against Chongqing and Yan’an. The Movement for the Rise of Asia and National Reconstruction disseminated its ideas through several Chinese-language periodicals. It already had a monthly publication, the Xingjian 興建 (Rise and Construction), and then added the daily newspaper Xin Zhongguo bao 新中國報 (New China Newspaper). Iwai equipped his newspaper with printing presses purchased from the Asahi Shinbun, thanks to his connections with the newspaper’s deputy editor-in-chief, Ōnishi Itsuki 大西斎 (1887-1947), who was also a Tōa Dōbun Shoin alumnus. Stung by Kagesa‘s about-face, Iwai sought to ensure that the military would no longer obstruct his efforts by getting closer to the influential commander Tsuji Masanobu, who was then deeply involved in mobilizing minds in the occupied zone. Too busy in Shanghai to visit the headquarters of the China Expeditionary Army (Shina hakengun 支那派遣軍) in Nanjing, Iwai was represented by Kodama Yoshio. Tsuji provided enthusiastic support and even wanted to appoint Iwai as the Supreme Advisor (saikō komon 最高顧問) to the Daminhui 大民會 (Great People’s Association), replacing Major General Matsumuro Takayoshi 松室孝良 (1886-1969) whom he considered ineffective. Iwai accepted, mainly for financial reasons as he acknowledges in his memoirs. However, Matsumuro refused to give up his position, forcing Iwai to coexist with him from his appointment in April 1940 until the dissolution of the Daminhui the following winter.

Moreover, he strove to improve his relations with his movement’s main adversary within the new government: Zhou Fohai. The latter was also aware that he had to reach an accommodation with Iwai. Following what appeared to be their first meeting on June 3, 1940, Zhou wrote in his diary: “It is better to befriend him than to make him an enemy.” For his part, Iwai considered, on the advice of Yuan Shu, offering Zhou an honorary director-general position of the Movement’s publications. This cordial relationship was reflected in the financial aid that Zhou, as Finance Minister, granted to the Movement for the Rise of Asia and National Reconstruction. On July 18, 1940, after promising a monthly payment of 30,000 yuan to Iwai’s organization, Zhou noted: “At least, this group is unlikely to oppose us henceforth.” While this method of buying the loyalty of forces outside Wang Jingwei‘s group had proven effective, it did not seem to yield results in the case of Iwai and Yuan Shu. Following a visit by the latter on August 11, 1940, Zhou expressed his anger: “They claim they want to be led by the government, but they stand apart from the GMD. Moreover, they claim they want to be under my patronage. However, I fear they only seek to take advantage of me temporarily, as this organization is used by the Japanese to hinder the GMD.” Yet, Zhou continued to want to “enlist them [wangluo 網羅],” as he wrote after a meeting with Iwai on September 22, 1940. He achieved his objective on December 17, 1940, when the Movement for the Rise of Asia and National Reconstruction announced its dissolution.

This dissolution took place in the context of the creation of the Chinese branch of the East Asian League Movement (Dongya lianmeng yundong 東亞聯盟運動) launched by Ishiwara Kanji. Indeed, to better promote Ishiwara’s movement in China, his disciple Tsuji Masanobu proposed as a counteroffer to Wang Jingwei that mass organizations previously established in Beijing (Xinminhui 新民會), Nanjing (Daminhui 大民會), Wuhan (He Peirong’s Republican Party), and Shanghai (Iwai’s Movement) should merge into the General Chinese Association of the East Asian League (Dongya lianmeng Zhongguo zonghui 東亞聯盟中國總會), led by Wang Jingwei. While the Xinminhui managed to circumvent the dissolution order thanks to the intervention of Army Minister Tōjō Hideki, Iwai’s organization did not escape it. Since mid-1940, it had been financially dependent not on the Gaimushō but on the Kōa-in, which was itself largely controlled by the Army. Powerless against the military, Iwai was torn between anger and shame at not having been able to prevent the efforts of the Chinese collaborators he recruited from going up in smoke. He likely also harbored some resentment against the Wang Jingwei group, which he did not spare from his criticism thereafter. Although the Movement for the Rise of Asia and National Reconstruction disappeared at the end of 1940, the influence of Iwai and the executives of his organization survived this disappearance, starting with that of his right-hand man Yuan Shu, who joined the central bodies of the Nanjing government and, a few months later, the administration of the Rural Pacification Campaign (qingxiang gongzuo 清鄉工作) directed from Suzhou by Li Shiqun.

Iwai remained a persistent thorn in the side of the Reorganized National Government, thanks in particular to the power of nuisance that his press group gave him. In addition to the titles previously mentioned, Iwai and Yuan Shu published the journal Xianzheng yuekan 憲政月刊 (Constitutional Government Monthly), which was renamed Zhengzhi yuekan 政治月刊 (Political Monthly) in January 1941 when the Nanjing constitutional project was abandoned. The betrayal of the promise made in March 1940 fueled critical articles by collaborators close to Iwai, including several communist agents such as Yuan Shu and Chen Fumu. A particularly incendiary long article by Iwai caused an uproar when it was published in March 1942 in Zhengzhi yuekan under the title “Guomin zhengfu de qianghua yu xin guomin yundong” 國民政府的強化與新國民運動 (The Strengthening of the National Government and the New Citizens’ Movement). Iwai did not hold back in his attacks against the Nanjing regime and its “orthodox” GMD, even going so far as to personally target Wang Jingwei: “When it returned to the capital, the National Government took on the guise of a cooperative effort involving the various parties and factions as well as non-partisan personalities. Subsequently, however, this government has unfortunately implemented a policy of centralized control. […] The GMD’s centralism gradually asserted itself, reaching a turning point with the establishment of the East Asian League Movement, leading in fact to a virtual dictatorship of the GMD. […] Ever since the dissolution of the various parties and factions, the GMD has acted in exactly the same way as the former GMD. […] President Wang’s position is progressively standing out and is the subject of a growing cult.” Moreover, Iwai broadly criticized the “selfish opportunism” of Chinese officials and the “custom of rising in public office in order to enrich oneself,” which he saw as obstacles preventing Wang Jingwei‘s government from gaining full support from Japan and “winning the hearts of the people.” Embracing the essentialist thesis on the lack of Chinese cohesion, Iwai asserted that “selfishness is one of the great defects of the Chinese nation.” These remarks provoked the fury of the leaders in Nanjing, foremost among them Zhou Fohai, who demanded and received apologies from Kagesa and the ambassador Hidaka Shinrokurō, who summoned Iwai to admonish him. Far from repenting, Iwai boasted of this reprimand in a report sent to Tokyo in August, to which he attached the Japanese version of the article, with the intention, he wrote, of improving a situation he deemed catastrophic.

Iwai’s interventionism in the political arena of the occupied zone also extended through the Tairiku Shinpō 大陸新報 (Continental News), the main Japanese-language daily in the occupied area which regularly published articles critical of the RNG. Iwai was well-acquainted with its director, Fuke Toshiichi 福家俊一 (1912-1987), whom he had assisted during the newspaper’s establishment in January 1939, alongside representatives from the Army and Navy, Kagesa and Commander Higo 肥後. Following the Japanese troops’ occupation of the foreign concessions from December 8, 1941, Iwai worked to revive two of Shanghai’s leading newspapers: the Shenbao and the Xinwenbao 新聞報. To head the editorial team of the former, Iwai brought over his friend Chen Binhe from Hong Kong, a seasoned journalist who had previously worked at the Shenbao in 1931. With Kagesa‘s support, he secured the green light from the Shanghai military authorities’ Press Bureau (hōdōbu 報道部). Lacking sufficient funds, he financed the paper’s launch with contributions from Satomi Hajime 里見甫 (1893-1965), a Tōa Dōbun Shoin graduate two years his senior, whom he had met through Inoue Isoji 井上磯次, a “continental adventurer” (tairiku rōnin 大陸浪人) with close ties to far-right circles. Iwai swore in his memoirs that he had no idea that Satomi, protected by Harada Kumakichi, was one of the main architects of the opium trade used by the Japanese army to finance the occupation of China. Satomi also handed over a one million yen check to Yuan Shu to support his activities. Simultaneously, Iwai helped the new editor-in-chief of the Xinwenbao, former Finance Vice-Minister Li Sihao 李思浩 (1882-1968), relaunch the daily after its journalists had fled, by dispatching Liu Muqing.

Iwai’s influence also extended to the field of education, an area he had been involved in since 1940 by funding study trips to Japan for young people selected from among the children and siblings of members of the Movement for the Rise of Asia and National Reconstruction. After a year of learning Japanese, the best among them took entrance examinations for Japanese universities. This ambition of Iwai’s, to prepare post-war Sino-Japanese friendship by educating Chinese youth, found an institutional framework with the establishment in June 1941 of the Institute for Self-Strengthening (ziqiang xueyuan 自強學院), a sort of Tōa Dōbun Shoin for Chinese students, which set up its premises in the Zhabei District 閘北區, north of Shanghai. Directed by Yuan Shu, the institution was presented by Iwai, in his inaugural speech, as intended to perpetuate the spirit of the Movement for the Rise of Asia and National Reconstruction, playing a comparable role to that held by the Huangpu Military Academy for the Chinese national revolution. In reality, it primarily produced Chinese auxiliaries for Japanese imperialism, although a number of them joined the CCP at the end of the war.

Students lived permanently at the Institute, which covered all of their expenses. In addition to lessons in Japanese, they received instruction in “military technique” (junshi shuke 軍事術科) and participated in physical exercise sessions. The curriculum included studies on Southeast Asia and its communities of overseas Chinese. In the context of escalating tensions with the United States, which culminated in the entry into war in December 1941, the Self-Strengthening Institute aimed to train Chinese agents capable of supporting the “southward advance,” particularly through their mastery of the regional languages of southern China (Cantonese and Minnan). Guest speakers, such as the bookseller Uchiyama Kanzō 内山完造 (1885-1959), a central figure in pre-war Sino-Japanese intellectual circles in Shanghai, would regularly give lectures. Additionally, emulating the Tōa Dōbun Shoin, study trips were organized in Jiangsu, especially from 1944 onwards, when Yuan Shu was appointed head of the Education Bureau (jiaoyuting 教育廳) of the provincial government.

The 31 students of the first class enrolled in August 1941 and graduated in June 1942. Several of them were immediately employed by Iwai’s Special Investigation Unit or joined the editorial team of the Xin Zhongguo bao. For instance, Ding Wenzhi 丁文治 (1921-1997) went on to become a distinguished journalist in post-war Taiwan, particularly at the Lianhebao 聯合報 (United Daily News). Others joined the work teams (gongzuotuan 工作團) of the Rural Pacification Campaign, where Yuan Shu was one of the principal officials. Furthermore, several students from Guangzhou, Shantou, or Xiamen contributed to the expansion of the Japanese empire in the South by disseminating Pan-Asianist propaganda among the Chinese diaspora, notably in Indochina, as exemplified by Yang Zhaokun 楊兆錕, who post-war managed a Hong Kong travel agency for Japanese tourists. A second cohort, also numbering 31 students, graduated in June 1944 after completing a two-year course.